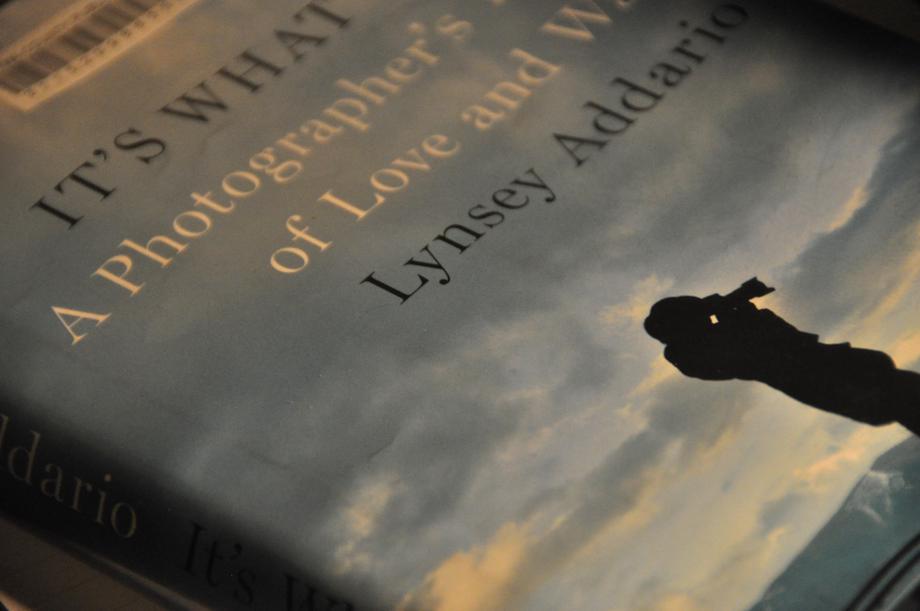

I just finished reading conflict photographer Lynsey Addario's book, It's What I Do. I admit that I judged the book by its title, which didn't stir much in me. My expectations were quickly derailed. She got into global photojournalism in her early 20s, was shooting in Afghanistan before the US military got there, and has been kidnapped twice.

This book resonated with me more than Robert Capa's autobiography, which I read pretty recently. Like Capa (or his girlfriend and colleague Taro), she was a part of a photojournalist community that formed close bonds with one another. Sometimes, she photographed things the American military considered sensitive, or would want to censor. She worried about her cameras and equipment even in the face of danger. She was often unable to take decent photos because of environmental stresses.

However, her challenges are more complex. This book is told through a woman's voice, working in a male-dominated profession. Her struggles with being taken seriously by soldiers and men in the Muslim world are relatable. The reporting aside, her experiences as a Western woman in the Muslim world are interesting stories on their own. Her insights about balancing relationships, marriage, pregnancy and motherhood, with the life of a foreign correspondent reveal her multi-faceted character.

On traveling to Afghanistan under the Taliban in 2000:

"I was an unmarried American woman who would want to photograph civilians. In Afghanistan, women were not allowed to move around outside the home without a male guardian. Photography of any living being was illegal. According one famous hadith, the Prophet Muhammad said: "Every image-maker will be in the Fire, and for every image that he made a sould will be created for him, which will be punished in the Fire." 1

On her motive and drive:

"I became fascinated by the notion of dispelling stereotypes or misconceptions through photographs, of presenting the counterintuitive." 2

"The difference between a studio photographer and a photojournalist was the same as the difference between a political cartoonist and an abstract painter [ . . .] Leaving at the last minute, jumping on planes, feeling a responsibility to cover wars and famines and human rights crises was my job. Not doing those things was the same as a surgeon ducking out of an emergency operation or a waitress refusing to bring a customer's plates to the table." 3

"I was now a photojournalist willing to die for stories that had the potential to educate people. I wanted to make people think, to open their minds, to give them a full picture of what was happening in Iraq so they could decide whether they supported our presence there." 4

"I knew then that I wanted to tell people's stories through photos; to do justice to their humanity, as Salgado has done; to provoke the kind of empathy for the subjects that I was feeling in that moment." 5

On her subjects in Darfur:

"I moved around the desert camp self-consciously, a white, well-fed woman trudging through their misery. The people understood that I was an international journalist, but I was still trying to figure out how to take pictures of them without compromising their dignity." 6

- Addario, Lynsey, It's What I Do: A Photographer's Life of Love and War (New York: Penguin Press, 2015), 55.

- Ibid, 93.

- Ibid, 108.

- Ibid, 172.

- Ibid, 36.

- Ibid, 179.